Good writing moves up and down the ladder of abstraction, ranging between vivid specifics at the bottom to intangible abstractions – such as love, friendship, betrayal – at the top. Hovering around the middle rungs makes writing dry and bureaucratic. Embracing the range helps you simplify the complex, and ensures that your prose touches both ground and sky!

What is the ladder of abstraction?

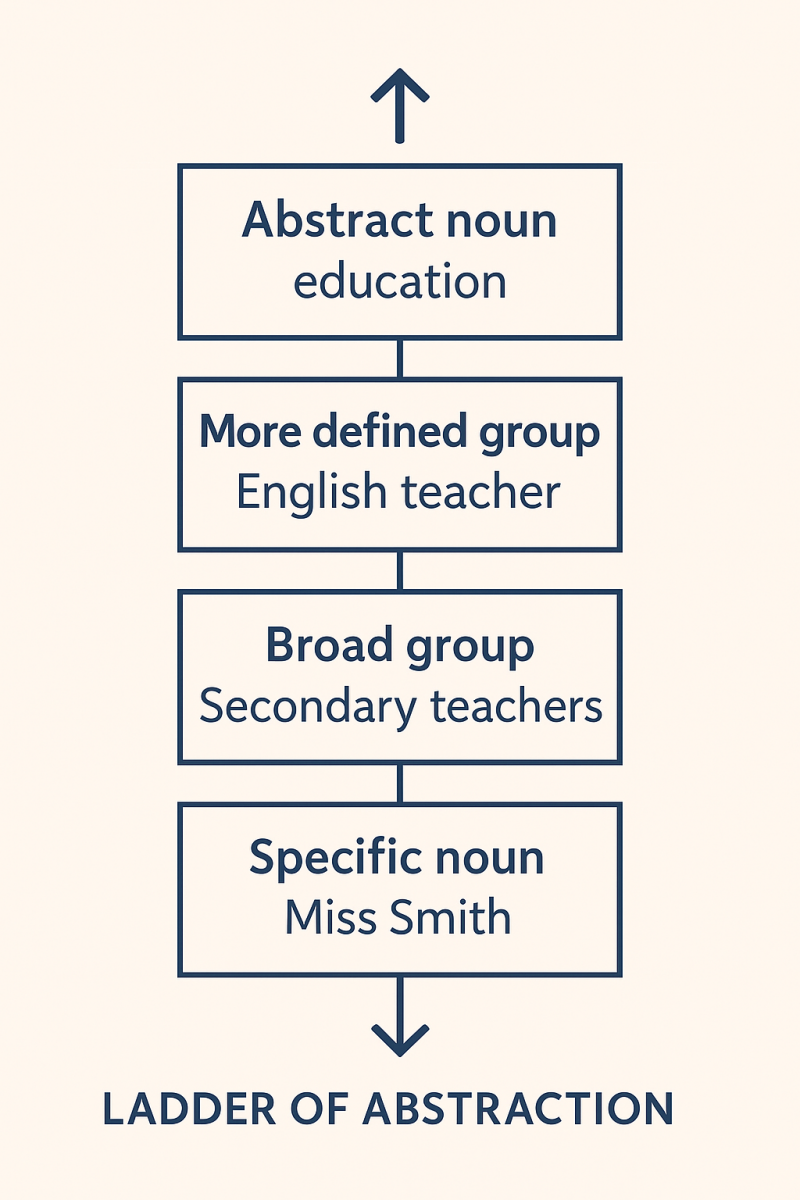

When we write, we're always making choices about how abstract or concrete our writing is going to be. In 1939 linguist S. I. Hayawaka described this range as the ladder of abstraction. At the bottom are precise, tangible features the reader can visualise. At the top are sweeping concepts and ideas. In between sit the broader categories: the 'middle rungs'. These can be useful but become a trap if you stay there too long.

Imagine a ladder. At the bottom you might write: Miss Smith. A little higher is secondary teachers. Higher still: English teacher. At the top: education.

If you want to make your writing more dynamic and engaging, then your goal is to move up and down this ladder. This gives your reader the grounding of concrete images and the perspective of big-picture meaning.

In his book Writing Tools Roy Peter Clark describes how the two nouns in ladder of abstraction exemplify this idea: the first noun – ladder – is concrete and sensory, while the second noun – abstraction – is intangible and more difficult to comprehend.

Why does movement matter?

- Stay at the bottom only and you risk drowning your reader in detail without giving them a sense of why it matters.

- Stay at the top only and you may sound lofty or vague.

- Hover in the middle and you can slip into the bland, lifeless territory of bureaucratic prose. The reader gets lost in a fog of managerial terms.

Bottom (concrete detail):

Miss Smith handed me a red-inked essay with ‘See me’ scrawled at the top.

Top (abstract):

Education changes lives.

Middle (bureaucratic):

Secondary-level staff provided formative assessment feedback to students.

See how these 'middle rungs', if overdone, can suck the life out of writing?

The two following examples show a 'middle rung' paragraph, followed by its made-over version!

Before (middle rungs):

The school’s teaching staff initiated a new cross-curricular literacy programme during the summer term. One member of staff, specialising in English instruction, implemented a non-classroom-based learning activity to facilitate creative engagement. This resulted in improved learner motivation and enhanced observational skills across the cohort.

After (all rungs):

Education changes lives. I discovered the power of teaching strategies the summer a new teacher came to our school – a woman with a tweed skirt, a quick laugh, and a bag that rattled with chalk. On her first day, Miss Smith told us to throw away the worksheets and follow her outside. We sat under the sycamore, writing poems about the ants marching over our shoes. Years later, I understood what she was really giving us – the courage to see the world in our own words.

Key:

Top (abstract)

Middle

Bottom (specific)

Three Tips

- Test one of your own paragraphs according to the rungs. Are you stuck in one area? Depending on your purpose, you might want to redraft, spanning the range of rungs.

- Identify the abstract nouns in your writing. For each one, give a concrete image.

- Now do the opposite: for every concrete detail ask 'So what?' and connect to an abstract idea.

The ladder of abstraction is a tool rather than a set of rules. By consciously shifting between its rungs, you can make your fiction more vivid and your nonfiction more engaging and persuasive. It works in any genre – the trick is to just keep moving!

Add comment

Comments